On 25 June 2024, the European Medicines Agency gave a thumbs up – in the form of a qualification opinion of novel methodologies for drug development – to a new methodology extensively validated by the IMI AMYPAD project that can assess the degree of Alzheimer’s disease visible in a person’s brain scan.

The endorsement means that the method can be confidently used in clinical trials by researchers who are seeking new treatments for Alzheimer’s disease – the methodology can help to evaluate how effective new potential treatments are.

The technique works by grading the level of Alzheimer’s disease a person has according to the amount of a protein called amyloid that is present in their brain, which is estimated using radioactive signals visible on a brain scan.

“Alzheimer’s disease is caused by a series of processes, the first one of which is amyloid deposition in the brain. This is a very early sign, a person probably starts accumulating amyloid 10-15 years before getting dementia,” says Frederik Barkhof, professor of Neuroradiology at VU University Medical Centre, Amsterdam and University College London, who was the academic lead of the AMYPAD project.

Amyloid in the brain is detected in two main ways – either by a spinal tap to draw cerebrospinal fluid for analysis, or by the much-less-invasive option of an amyloid PET scan, where the patient is injected with a radioactive tracer specifically targeting the protein and then undergoes a brain scan. The radioactive tracer attaches to amyloid plaques in the brain, and because they are radioactive, they appear as brightly coloured in the resulting brain scan.

Up until now, clinicians have looked at the scans and drawn subjective conclusions on how developed a person’s Alzheimer’s pathology is according to what they see.

However the Centiloid method evaluated by the AMYPAD project seeks to standardise that approach, defining exactly what quantity of radioactive tracer visible on the scan corresponds to each level of cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s Disease.

“We can create a map of the affected brain areas and then we count the radioactivity on that map,” says Gill Farrar, scientific director at GE Healthcare Life Sciences, who was the project lead of AMYPAD on the industry side.

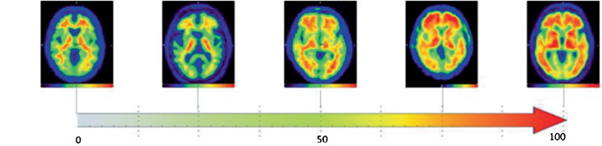

“Next we compare the images generated in healthy control subjects to those that have different levels of cognitive decline due to the presence of the Alzheimer’s disease proteins – that gives us an overall measure of how much amyloid is present. Rather than just indicating the presence or absence of amyloid, the quantification allows you to have a continuous measure over the Centiloid scale. Somebody with a healthy brain will have a score that’s between zero and twenty-five, whereas someone with full-blown Alzheimer’s will have 100.”

Left to right: A healthy brain at zero, the brain of a person with highly developed Alzheimer's at 100

While the Centiloid method will help improve the initial diagnosis of patients, it can also be used by researchers to evaluate how well new treatments to combat Alzheimer’s are working.

“There are treatments being developed for Alzheimer’s which remove amyloid plaques from the brain,” says Barkhof. “When this works, there is less amount of radioactive tracer visible on the scan. People can return to an almost normal scan, so – using the Centiloid scale – the effect of the treatment can now be measured.”

Support for the qualification opinion came largely as a result of research carried out by the AMYPAD project.

The AMYPAD team highlighted the need to reliably quantify amyloid, provided datasets to back up this need and highlighted how Centiloid thresholds could help better define the progression of Alzheimer’s – for instance, a Centiloid value of more than 20-30 might indicate the early stages of pathological Alzheimer’s. The robust data provided by the project were able to satisfy the EMA’s stringent requirements and the scale could potentially be used by clinicians in the future to more objectively diagnose Alzheimer’s disease.

“The qualification opinion is a regulatory endorsement of this methodology,” says Farrar. “It lends credibility for it to be used as an outcome measure in clinical trials, and it’s a stepping stone to routine use by clinicians.”

AMYPAD is supported by the Innovative Medicines Initiative, a partnership between the European Union and the European pharmaceutical industry.